In a previous blog, I wrote about the current state of cycling in the UK drawing largely upon a previous large-scale study I was involved with – Understanding Walking and Cycling. I highlighted that cycling in most UK cities tends to be dominated by young, male, white, ‘hardened’ cyclists – what I called the ‘velomobile elite’. They are the product of a predominantly car based system that marginalizes cycling and also places the onus on cyclists to develop the capability to ride fast and assertively and to do so wearing full protective gear. This stems from a ‘vehicular cycling’ philosophy of planning for cycling in the UK (and the USA) which is based on the assumption that, ‘cyclists fare best when they act and are treated as drivers of vehicles’ using the same road space – have a look at this video for an illustration. The way that cycling is performed on city streets often looks more like sports cycling (‘Criterium racing’ perhaps!) than an ordinary, everyday way of moving around. It is the adoption of the vehicular cycling principle and the perpetual acclimatization to current hostile cycling conditions that has shaped British cycling identities and practice and has done much to deter the majority of the public from the very idea of ‘becoming a cyclist’.

In a previous blog, I wrote about the current state of cycling in the UK drawing largely upon a previous large-scale study I was involved with – Understanding Walking and Cycling. I highlighted that cycling in most UK cities tends to be dominated by young, male, white, ‘hardened’ cyclists – what I called the ‘velomobile elite’. They are the product of a predominantly car based system that marginalizes cycling and also places the onus on cyclists to develop the capability to ride fast and assertively and to do so wearing full protective gear. This stems from a ‘vehicular cycling’ philosophy of planning for cycling in the UK (and the USA) which is based on the assumption that, ‘cyclists fare best when they act and are treated as drivers of vehicles’ using the same road space – have a look at this video for an illustration. The way that cycling is performed on city streets often looks more like sports cycling (‘Criterium racing’ perhaps!) than an ordinary, everyday way of moving around. It is the adoption of the vehicular cycling principle and the perpetual acclimatization to current hostile cycling conditions that has shaped British cycling identities and practice and has done much to deter the majority of the public from the very idea of ‘becoming a cyclist’.

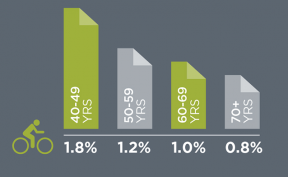

Older cycling in the UK is a victim of this. 73 per cent of those aged 65 and over think it is too dangerous for them to cycle on British roads compared to 43 per cent of those aged 18-24 (British Social Attitudes Survey, 2012). This is one of the main reasons why the share of journeys made by bicycle in the UK is low but particularly low for older age groups.

Only 1 per cent of all journeys made by people aged 65 and above in the UK are by bicycle.

This compares to 9 per cent in Germany, 15 per cent in Denmark and 23 per cent in the Netherlands (Pucher and Buehler, 2012).

This compares to 9 per cent in Germany, 15 per cent in Denmark and 23 per cent in the Netherlands (Pucher and Buehler, 2012).

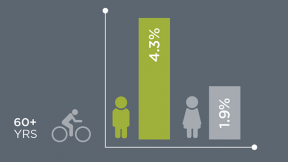

There is also gender disparity in the UK with older men twice as likely to cycle as older women.

There is also gender disparity in the UK with older men twice as likely to cycle as older women.

The cycle BOOM study is providing a deeper understanding of the experience and potential of older velomobility in the UK. We have been working with many older cyclists who continue to cycle, or are attempting to re-engage with cycling, despite the odds. They are very much a minority-within-a-minority (especially outside of our Oxford case site). So what might a society that supports older cycling look like?

Recently, Ben Spencer and I were invited to contribute to a publication by The Oxford Institute for Population Ageing focusing on the concept of Intergenerational Contact Zones (ICZ). We are tasked with imagining how this might apply to cycling and how it could help professionals across different sectors. Our brief was that the term ICZ can be used in two ways: literally (referring to the actual space(s) in which different generations meet) and conceptually (referring to a multi-dimensional understanding about that space) – efforts to define ICZ can be found here.

I have to admit, I had never heard of this concept before! The development of the concept of ICZ stems from a desire to develop a framework for investigating and designing spaces that engage and encourage interaction between younger and older people and also establish them as a more visible presence in contemporary society. This is important within a society that is ageing and where there is a growing childhood obesity epidemic. For example, applying the notion of ICZ to cycling could help reduce social isolation and encourage social inclusion; ensure the safety of vulnerable members of the community and improve connections to activities across local neighbourhoods and the wider town or city; provide opportunities for active living; break down ageist social norms (e.g. ‘cycling is not for older people’ and ‘children should be seen and not heard!’). It also helps us to refocus attention away from an apparent obsession with the dominant ‘middle years’ of the life-course, namely those engaged in production and consumption (i.e. commuting and doing business), towards those ‘not of working age’.

Thinking about cycling through the lens of Intergenerational Contact Zones might also help us to imagine how we can encourage harmony between age groups and reduce generational conflict (among all types of road users). This could for example, help us to think about ways of engaging older and younger people in the design of cycle infrastructure (and research on cycling). A vision for intergenerational cyclescapes in an urban setting might, for example, encourage more civilised ‘smoother cycling’ mediated by functional (as opposed to ‘sports’) bicycles; provide opportunities for intergenerational riding together; enhance cooperation between riders and other road users; cater for different cycling capabilities and therefore be more ‘forgiving’; encourage ‘intergenerational intelligence’ through programmes that foster appreciation of how it is to cycle from the perspective of ‘the other’.

A broader diversity of people of all ages and wages moving around in urban areas on bicycles, instead of travelling short distances in private cars, could create positive social interaction. This could help to promote understanding – the person on that bike could be your older relative – and reshape the image of cycling as something that is multi-generational and for all. It could finally start to break down the negative image of cycling harboured by some of the British public and promulgated by large sections of the British media.

It is still early stages but we will keep you updated on how our thoughts unfold.

Tim Jones is the Principal Investigator on the cycle BOOM research project at Oxford Brookes University. Contact him at tjones@brookes.ac.uk

Leave a Reply